It was the film, “Kiss of the Spider Woman,” that first inspired my interest in Twin Hero psychology. The film features two male protagonists: Molina, a romantic homosexual, and Valentin, a driven political prisoner. The two heroes, opposites in nearly every way, are required to share a prison cell, where they each must compromise their hard-held ideals in order to gain compassion for each other. Throughout their ordeal, Molina entertains and eventually seduces Valentin by recounting the story of the “Spider Woman,” a wartime romance set in Nazi Germany.

It was the film, “Kiss of the Spider Woman,” that first inspired my interest in Twin Hero psychology. The film features two male protagonists: Molina, a romantic homosexual, and Valentin, a driven political prisoner. The two heroes, opposites in nearly every way, are required to share a prison cell, where they each must compromise their hard-held ideals in order to gain compassion for each other. Throughout their ordeal, Molina entertains and eventually seduces Valentin by recounting the story of the “Spider Woman,” a wartime romance set in Nazi Germany.

I recalled that Spider Woman was a central character in Navaho mythology and wrote Don Sandner, author of Navaho Symbols of Healing (1979), asking if he could give me some insight into her character. He responded, directing me to a little-known book, first published by Bollingen in 1943, in which Spider Woman figures prominently.

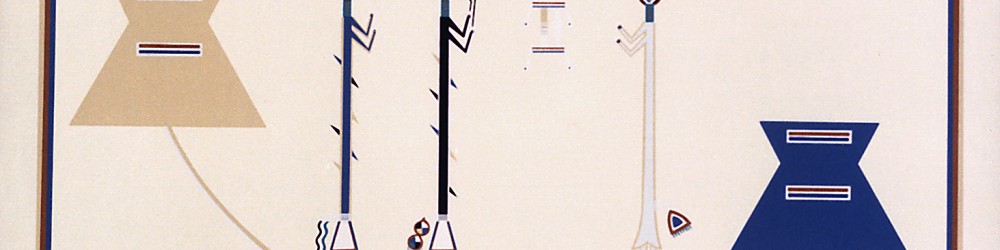

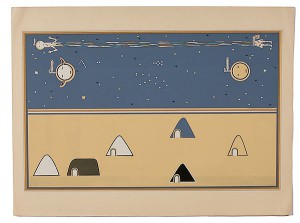

This book, Where the Two Came to Their Father, contains Joseph Campbell’s first published commentaries in the field of comparative mythology. Campbell’s illustrious career was launched here, with his tremendously well-developed insights into the central Navajo legend. The myth had been recorded for the first time by artist Maud Oakes, under the direction of Navaho medicine singer Jeff King. Oakes meticulously reproduced the eighteen sand paintings depicting the journey of the twin boys, Monster Slayer and Child Born of Water.

Spider Woman appears in the myth as an ambivalent deity, both good and bad, sometimes helping and sometimes hindering the twins on their journey to the house of their father. The fourth of the sand painting series depicts the twins on either side of a feather given them by Spider Woman for protection and strength; yet we come to learn that Spider Woman stole this feather from the boys’ Sun Father. In the film, “Kiss of the Spider Woman,” Leni the Spider Woman represents primarily the negative aspects of Spider Woman’s potential characteristics. As the film progresses, Leni increasingly becomes an idealized feminine figure that serves to distort both men’s experience of the actual feminine.

Spider Woman appears in the myth as an ambivalent deity, both good and bad, sometimes helping and sometimes hindering the twins on their journey to the house of their father. The fourth of the sand painting series depicts the twins on either side of a feather given them by Spider Woman for protection and strength; yet we come to learn that Spider Woman stole this feather from the boys’ Sun Father. In the film, “Kiss of the Spider Woman,” Leni the Spider Woman represents primarily the negative aspects of Spider Woman’s potential characteristics. As the film progresses, Leni increasingly becomes an idealized feminine figure that serves to distort both men’s experience of the actual feminine.

Like Valentin and Molina, the Navaho Twins, Monster Slayer and Child Born of Water, represent the physical and the spiritual aspects of the masculine, respectively. Campbell describes the twins as the counterpoised parts of a powerful dialectic:

The two, Sun-Child and Water-Child, antagonistic yet cooperative, represent a single cosmic force polarized, split and turned against itself in mutual portions. The life-supporting power, mysterious in the lunar rhythm of its tides, growing and decaying at a time, counters and tempers the solar fire of the zenith, life desiccating in its brilliance, yet by whose heat all lives (1936:36).

The color blue is associated with the second twin, Child Born of Water, who plays a key role in compensating the aggressive nature of his warrior brother. In the sand painting series, the twins appear to be identical in both form and color until the pivotal point of transformation, when their Sun Father bestows upon them their proper names, at which time they gain their individual colors and powers. Thereafter, Monster Slayer and Child Born of Water are represented in the sand paintings by their respective colors, black and blue. Campbell attributes the ultimate success of the Twin Heroes to the blue twin’s mitigating influence,

“…one cannot help but feel…that it is largely the balancing presence of Child Born of Water which guarantees the benevolent end of [their] martial labors” (1969:36).

They myth of Monster Slayer and Child Born of Water recalls us to the cross-cultural archetype of the Twin Heroes, a further unfolding of the Western Hero archetype which we tend to equate with masculinity. As represented by Hercules and other heroes in many of our best known myths, masculinity emphasized doing rather than being, or pure action without a basis in understanding. Yet, if we dig deep enough into the mythology of virtually any world culture, we will find that the central male Hero was originally a twin. This phenomenon is so pervasive that it has led psychologist Edward Edinger to assert that “… the individuated ego is destined to be born a twin” (1986:36). It is, for example, a little known fact that even Hercules was born with a twin named Iphicles (Slater, 1968:381-383).

They myth of Monster Slayer and Child Born of Water recalls us to the cross-cultural archetype of the Twin Heroes, a further unfolding of the Western Hero archetype which we tend to equate with masculinity. As represented by Hercules and other heroes in many of our best known myths, masculinity emphasized doing rather than being, or pure action without a basis in understanding. Yet, if we dig deep enough into the mythology of virtually any world culture, we will find that the central male Hero was originally a twin. This phenomenon is so pervasive that it has led psychologist Edward Edinger to assert that “… the individuated ego is destined to be born a twin” (1986:36). It is, for example, a little known fact that even Hercules was born with a twin named Iphicles (Slater, 1968:381-383).

Anthropologist Paul Radin has called the Twin Heroes the basic myth of the American Indians.

The constituent elements of this myth, the plot themes and motifs are found distributed fairly unchanged over an area extending from Canada to southern South America and from the Pacific to the Atlantic Ocean. Because of this wide distribution and because of the importance attached to it everywhere, I feel it is not an exaggeration to designate it as the basic myth of aboriginal America (1950:359).

The emergence of twin heroes in Native American mythologies indicates a radical shift in the culture and, by implication, individual consciousness. In Western patriarchal tradition, the sacrifice or suppression of the second twin indicates a deliberate repression of the yielding, balancing influence of the lunar masculine principle, represented in the Navaho myth by the blue twin, Child Born of Water. The “lunar” qualities—tenderness, receptivity, intuition, compassion—have been feminized or homosexualized in Western Culture. The character Molina, in “Kiss of the Spider Woman,” epitomizes this phenomenon. Even though Molina is homosexual and very feminized, if you look beyond the sexual issue, you can envision Molina and Valentin as representative of dual aspects of the masculine, the physical and the spiritual, the solar and the lunar.

The lunar masculine is present in male moon gods, such as Dionysus and Osiris, who embody the dying and resurrecting nature of the masculine; Sinn from Babylonia; and the maternal Talking God of the Navaho. We also come upon the lunar masculine in the Kundalini chakra system, in the “soma” chakra. Mush of my research focuses on this prerequisite step of hooking up solar and lunar masculine energies in a preliminary “union of the same” in the ego, before engaging in a “union of opposites” with the dual feminine in the unconscious. In his alchemy research, Jung did not sufficiently emphasize the significance of this “union of the same” step, represented in a plate showing two men joined in one body (1970:508).

The “union of the same” requires that a man consciously, actively, seeks to reclaim his twin energy. The first step toward manifesting this ego-strengthening union is to remove the gender labels from the entire range of behaviors that are available to men: instead of masculine and feminine, yang and yin, we can envision a solar and lunar dialectic operating in both the ego and the unconscious. The ego may have resistance to this renaming, but the unconscious is immediately responsive. This simple psychological switch has profound energetic consequences. To reorient around the organizing principles of Sun and Moon, rather than Masculine and Feminine, frees both men and women from the restrictive categories that have denied men a full range of behaviors and have required that women carry the full lunar energy.

Shiva as Nataraja embodies the solar and lunar qualities of the masculine. Nataraja’s dance symbolizes the rhythm of the universe and the cycles of creation and destruction.

Many solutions to the outmoded notion of “solar” masculinity continually fail to capture the imaginations and psychological energies of men. Men are resistant to alternative solutions which, in encouraging them to become “more like women,” imply that they must sacrifice their masculinity. Not surprisingly, our society still seems to be in search of a new view of masculinity, a new image of the heroic. I encourage our seeking a new vision of masculinity in the archetype of the Twin Heroes. The sacred twins, like many other mythic heroes, Christ, Osiris, and the Buddha among them, are by their very nature sacrificial; they give of themselves freely to those individuals who approach them with a deeply curious mind and an open heart.

References

Campbell, Joseph and Maud Oakes. Where the Two Came to Their Father. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, Bollingen Series I, 2nd edition, 1969

Doty, William. “Monster Slayer and Child Born of Water: Complimentary Twin Sibs in Native American Psychomythology,” presented at the Society for Values in Higher Education Annual Meeting, Colorado College, August 1989.

Edinger, Edward F. The Bible and the Psyche: Individuation Symbolism in the Old Testament, Toronto, Canada: Inter City Books, 1986.

Jung, Carl Gustav. Mysterium Coniunctionis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, Bollingen Series XX, 2nd edition, 1970.

Levy-Bruhl, Lucien. “How Natives Talk,” How Natives Think, by Lillian Clare. New York: Washington Square Press, 1966.

Puhvel, Jaan. Comparative Mythology. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987.

Radin, Paul. “The Basic Myth of North American Indians,” Eranos-Jahrbuch 1949, ed. Olga Frobe-Kapteyn. Zurich, Switzerland: Rhein-Verlag, 1950.

Slater, Philip E. The Glory of Hera. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1968.