You yourself are even another little world and have within yourself the sun and the moon and also the stars. -Ongen

The fragmenting of the human image of the divine into gods versus goddesses and consequently masculine versus feminine is a long-standing state of affairs. Beginning as early as 5000 B.C.E. with the beginning of the Bronze Age and gradual substitution of the male god for the goddess, then intensifying in the Judeo-Christian era with the identification of Christ as son and God as father, we have inhabited a world where male and female are seen as opposite poles of human existence.

Within this opposition, the masculine came to dominate, associated increasingly with the sun, or the logical and rational, and the female with the moon, or the emotional and the irrational. To redress this imbalance, feminists have reasserted the importance of the goddess or feminine principle. While the work of these scholars is indeed significant, emphasis on the goddess pantheon inadvertently perpetuates the polarization of our worldview. No matter how many adherents feminists gain, our universe will remain split, the battle lines drawn between gods on the one hand, and goddesses on the other. Perhaps it is time to end gender warfare, to ask ourselves if it is possible to transcend the gender associations we continue to project onto the universe. Perhaps we can creatively return to an older, more basic, mythology, one appropriate to our own time and place, by replacing the masculine and feminine attributions of god and goddess, with the sun and the moon themselves—the objects these attributions were originally intended to describe.

The sun and the moon have been central to many spiritual systems. A brief survey of world mythologies demonstrates that attributions of masculine and feminine are in no way inherent to these objects. Rather, these gender specifications are cultural and political artifacts, projections not only of particular cultures but also of specific developmental moments within particular cultures.

In Pygmy culture, the molimo, the most sacred ceremony, said to have survived from the Paleolithic era, celebrants pray to the divine moon: Mother moon, mother, mother, here us, mother, come. But at the tip of Siberia, the Chukehi reindeer herders recognize the Moon Man as the first to agree to light the sky and measure seasonal changes and the yearly cycle. The Eskimos also know the moon as male, calling him Brother. And the Mataco Indians of Northern Argentina, as in most tribal cultures, associate a woman’s menstrual cycle with the male moon god who monthly deflowered mortal woman. Indo-European cultures introduced images of the Man in the Moon, but all the Greek goddesses are moon goddesses. Even the Hebrew Father-god, according to scholar Robert Briffault, was mostly likely derived from a local moon-god.

Gender references to the sun are equally varied. We are most familiar with masculine sun gods, such as the Greek Helios and Hyperion, the Japanese Buddha, and, of course, Christ, born on the winter solstice and often referred to as Sol Invictus (Unvanquished Sun, Light of the World). There also is, however, a litany of sun goddesses. The Japanese Shinto goddess, Amaterasu, is the Great Heaven Illuminating Deity; Sunna and Grain are the Celtic and Nordic goddesses of the sun; the Germans refer to Fran Sonne; and in the earliest tradition of the North American Indian tribes, the sun was feminine.

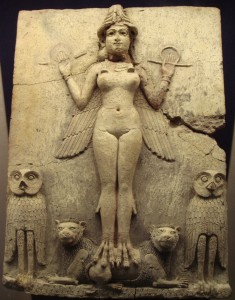

For the Sumarians of Mesopotamia, within one time frame, the moon was perceived as both male and female, with the moon goddess Inanna.

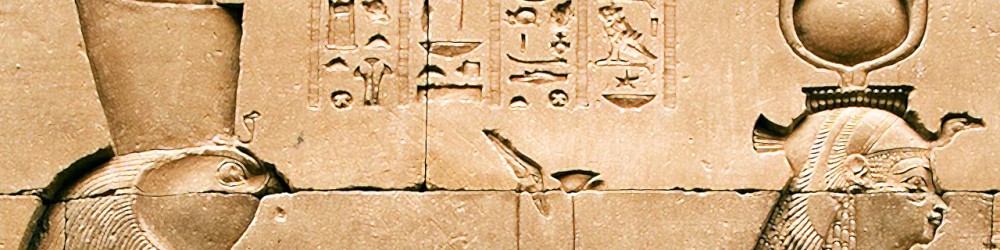

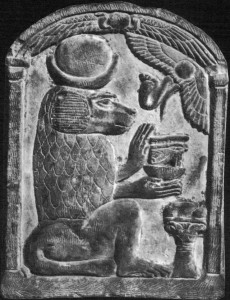

In addition to the genders of the sun and moon alternating from culture to culture, there is evidence that these attributions also varied withincertain cultures. For the Sumarians of Mesopotamia, within one time frame, the moon was perceived as both male and female, with the moon goddess Inanna born from the marriage of Nana and Ningal, a moon god and goddess, respectively, who also gave birth to Utu, the sun god. The Egyptian pantheon incorporates both moon gods and goddesses: Khones is depicted wearing a headdress of the moon disc and crescent; Thoth, the divine scribe, or god of knowledge and writing, carried the sickle (symbol of the new moon) in his hand; Osiris, the good of resurrection and rebirth, was also associated with the sickle; and Isis, the most important of the female deities, wore a sun disk resting upon a moon crown. This same horned moon crown and sun disk appear as the headdress of Harthor, the Lady of Heaven, or goddess of love and pleasure. Within the same pantheon, the sun appears in its primal manifestation as the lion-headed goddess Sekhkmet, seated with the sun disk on her head; Re is a male solar deity as well as the winged beetle, Khepera and the ram-headed god, Khnemu.

In the highly-industrialized Western world, we have moved so far from nature and our original relationship to the universe that we rarely think of the sun and moon as the entities and energies that served as the central organizing principles for the projection of male and female deities. The sexualizatoin of the universe into male and female has become the foundation for understanding the psychological, moral and ethical behaviors of men and women. Masculine and feminine qualities are embedded in the male-solar, female-lunar dichotomies. We should see solar and lunar not as metaphors for the genders, but as dimensions that modify gender, appearing as polarities within masculinity and femininity. If we continue to associate intuition and emotion with the feminine, and independence, reason, and assertiveness with the masculine, we will fail to explore the possibilities of the solar-feminine and the lunar-masculine, and we limit ourselves as human beings and fractionalize the universe. As Theodore Roszak says in Voices of the Earth, “There will be no peace in the battle of the sexes and no ecological sanity until we finally have done with the nonsense of sorting human virtues into masculine and feminine bins.”

by Howard Teich