Solar and Lunar Aspects of the Masculine

The universal theme of twin male heroes is documented in the mythologies of nearly every culture: it can be easily spotted in African, Mayan, Roman, Greek, and Eastern Indian mythologies. We are most familiar with the rivalrous male twins, like Romulus and Remus, and Jacob and Esau, but many other examples of twin boys, amicable as well as rivalrous, abound.3

Many solar/lunar twin male couples remain buried in the annals of history, largely because the lunar twin has been suppressed since the solarization of our mythology. It is seldom recalled, for example, that even Hercules was born a twin. Few records exist to illuminate the relationship between Hercules and his brother, Iphicles, but the fact that Iphicles existence was for the most part suppressed suggests that their relationship may have been rivalrous. It is probable that Iphicles, whose name implies strength, was at one time a hero in his own right.4

The Twin Heroes motif is featured in nearly all New World mythologies. Jung’s colleague, anthropologist Paul Radin, proclaimed the legend of the Twin Heroes the basic myth of the American Indians:

The constituent elements of this myth, the plot themes and motifs, are found distributed fairly distributed fairly unchanged over an area extending from Canada to southern South America and from the Pacific to the Atlantic Ocean. Because of this wide distribution and because of the importance attached to it everywhere, I feel it is not an exaggeration to designate it as the basic myth of aboriginal America.5

Campbell’s treatment of the Navajo solar/lunar twins may represent one of his most unique contributions to the anthropology of the human soul. Rarely do we come across such a precious example of oral literature that has not already undergone extensive acculturation at the hands of well-meaning anthologists. Artist Maud Oakes recorded the legend and sand paintings directly under the supervision of Navajo “Singer” Jeff King.

The original folio contains an almost complete record of an initiation process, indeed one of the most complete we have. It permits us the rare privilege of seeing how a young man, actively immersed in the imaginary heroic journey, may transcend the limitations of both solar and lunar aspects of his ego.

Campbell regarded the Navajo twin heroes, Monster Slayer and Child Born of Water as instrumental symbols, pointing us toward and perhaps helping to further our progress toward a resolution of limiting conflicts. The story of their journey, from the house of their mother Changing Woman to the house of their Sun-father, may represent Campbell’s most comprehensive example of his monomythic hero’s journey. The three stages he elucidates in The Hero with a Thousand Faces—Separation, Initiation, and Return—are fully developed here, not only in the text but even more dramatically in the series of eighteen sand paintings depicting the twins’ progress.

To anyone who, like Campbell, seeks to learn what is already known to many cultures of the world, the sand paintings present a rare opportunity for meditative insight. The male individuation process, so often eloquently described, is rarely inscripted so exactly in the language of the unconscious mind. Through imagery and symbols, the series of sand paintings allow for the meditative mind to participate in a unique and uplifting journey.

Where the Two Came to Their Father was recorded along with an account of the Navajo creation story that sets up the preconditions for the birth of twin males. Jeff Kings “Introductory Legend” describes how a rift develops between the sexes. As in many creation myths, like our own Judeo-Christian story of Adam and Eve, the original, paradisal relationship between Man and Woman falls into discord. In this Navajo version of the universal motif, a quarrel between the First Man and the First Woman results in a long separation of the sexes. The rather misogynistic story line describes how the women, who cannot bear the loneliness any longer, masturbate with cacti and sticks, and give birth to Monsters that run rampant through the world.

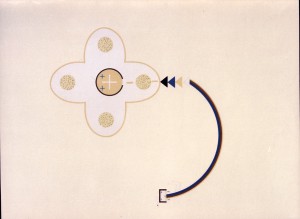

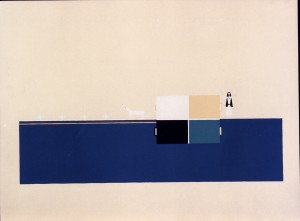

At the outset of the masculine initiation myth, the twin heroes emerge for the eventual purpose of ridding the world of its Monsters. The solar/lunar twins are born of a human mother, Changing Woman, and a divine father, the Sun, who impregnates her through the divine agencies of sunlight and dripping water. The first sand painting of the series shows the twins as yet undifferentiated in form and color. In this first stage of their heroic journey, the Separation, they are about to set out on their journey to the House of their Sun-father, who might aid them in destroying the Monsters.

The second, third, and fourth sand paintings portray the series of dangers and obstacles  the twins encounter on their way to the House of the Sun. Paul Radin emphasizes the importance of mythic twin heroes working together to achieve their common purpose:

the twins encounter on their way to the House of the Sun. Paul Radin emphasizes the importance of mythic twin heroes working together to achieve their common purpose:

Each twin constitutes only half an individual psychically. It is because the two are only complementary halves that they have always to be forced into action. … Each alone can do nothing positively. … For constructive and integrated activity … the two halves must be united. 6

Within the story, the twins must discover their unique talents and find the proper balance of combined action that will help them attain their common goals. In the individuating male psyche, this process of integrating the solar/lunar aspects of the ego also represents the first leg of the journey. While in this first segment, the solar/lunar twins’ actions remain undifferentiated, we can already begin to see how their combined activity encompasses both the “solar” and “lunar” styles of heroism that they eventually develop. Monster Slayer’s style of “solar” heroics resembles that of our own contemporary superheroes. Child Born of Water’s type of heroism, however, is different from that of the solar “conqueror” which we have come to equate with masculinity. The lunar twin becomes representative of a process of learning, of trial and error, of patience and negotiation that allows for the healing and reconnection of opposed forces. Psychologically, the lunar-masculine energy does not “replace” the solar-masculine, but works in conjunction with it.

Within the story, the twins must discover their unique talents and find the proper balance of combined action that will help them attain their common goals. In the individuating male psyche, this process of integrating the solar/lunar aspects of the ego also represents the first leg of the journey. While in this first segment, the solar/lunar twins’ actions remain undifferentiated, we can already begin to see how their combined activity encompasses both the “solar” and “lunar” styles of heroism that they eventually develop. Monster Slayer’s style of “solar” heroics resembles that of our own contemporary superheroes. Child Born of Water’s type of heroism, however, is different from that of the solar “conqueror” which we have come to equate with masculinity. The lunar twin becomes representative of a process of learning, of trial and error, of patience and negotiation that allows for the healing and reconnection of opposed forces. Psychologically, the lunar-masculine energy does not “replace” the solar-masculine, but works in conjunction with it.

Throughout the twins’ journey, while Monster Slayer is equal to any physical obstacles the twins might encounter, it is the lunar twins patience and thoughtfulness that permit them to solve the sticker problems.7 In the episode illustrated in the second sand painting, it is the brand of “lunar heroism” that Child Born of Water eventually develops which serves to accomplish their objective. The twins overcome their first monster not by means of physical force, but by “seducing” the creature through songs and prayers:

The songs and prayers to the monster showed that the heroes include in the field of their wisdom an understanding of the cosmic dignity of this guardian creature, had gone past him … in their knowledge, and thus were able to go past him in deed. (“Commentary” 70)

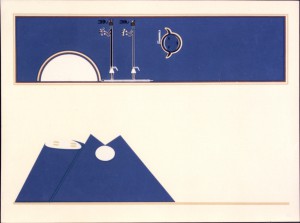

Up to now, the solar/lunar ego has been healing childhood wounds and mastering the complexes associated with childhood. The fourth sand painting depicts the twin heroes standing on the edge of the world ocean that they must cross to reach the house of their Sun-father. Here the twins pause on the edge, uncertain that they have the resources needed to travel from the earth-realm of their mother to the sky-realm of their father. Their going further requires taking a leap of faith in themselves, that they have the fortitude to handle whomever they may encounter. At this point in the analogous psychological process, the solar/lunar male ego is entering the next level of the unknown, which Jung called the collective

Up to now, the solar/lunar ego has been healing childhood wounds and mastering the complexes associated with childhood. The fourth sand painting depicts the twin heroes standing on the edge of the world ocean that they must cross to reach the house of their Sun-father. Here the twins pause on the edge, uncertain that they have the resources needed to travel from the earth-realm of their mother to the sky-realm of their father. Their going further requires taking a leap of faith in themselves, that they have the fortitude to handle whomever they may encounter. At this point in the analogous psychological process, the solar/lunar male ego is entering the next level of the unknown, which Jung called the collective  unconscious. To enter the collective unconscious, the realm of archetypal forces, the solar/lunar ego must be developed enough to remain firm, lest it be overwhelmed by the powers of the archetypes.

unconscious. To enter the collective unconscious, the realm of archetypal forces, the solar/lunar ego must be developed enough to remain firm, lest it be overwhelmed by the powers of the archetypes.

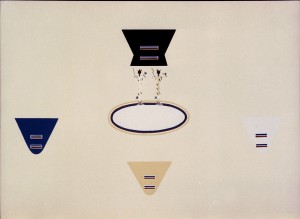

The fifth sand painting shows the twins having safely arrived at the house of the Sun. Here, in the “initiation” stage of the monomyth, the twins learn the powers of the archetypes and gradually gain strength as they encounter them. The first archetype the male ego encounters here is the feminine, or anima, represented as the Suns daughter. She greets her brothers and, after a few tests of her own, she presents them to their Sun-father, who puts them through a series of trials to determine if they are his true sons. The father of the solar/lunar twins also has as his constant companion a lunar counterpart, Water Carrier. Campbell’s earlier characterization of the solar/lunar twins is nearly identical to his description of their fathers:

The fifth sand painting shows the twins having safely arrived at the house of the Sun. Here, in the “initiation” stage of the monomyth, the twins learn the powers of the archetypes and gradually gain strength as they encounter them. The first archetype the male ego encounters here is the feminine, or anima, represented as the Suns daughter. She greets her brothers and, after a few tests of her own, she presents them to their Sun-father, who puts them through a series of trials to determine if they are his true sons. The father of the solar/lunar twins also has as his constant companion a lunar counterpart, Water Carrier. Campbell’s earlier characterization of the solar/lunar twins is nearly identical to his description of their fathers:

[Water Carrier] is the representative of that unpredictable, tidal sap-power, which is the polar opposite to the regular passing fire of the sun, and yet collaborates with the sun in the maintenance of the world-process. Sun-Father and Water-Father, Fire-Man and Moisture-Man: together they are discovered in the House of Strength; together they test the heroes who are to serve the cause of life. (“Commentary” 73)

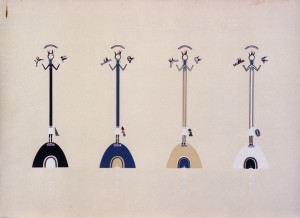

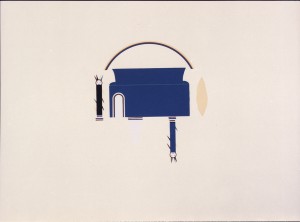

Water-Carrier is instrumental in assisting Sun-Father in administering the series of trials through which the twins prove their worthiness. In the sand paintings series, the twins have thus far remained identical in both form and color. The sixth painting depicts the pivotal point of transformation, where Sun-Father and Water-Carrier bestow upon the boys their proper names. It is at this moment also that they gain their individual colors and powers. Psychologically, this is the point at which the male ego becomes conscious of its dual nature. Hereafter, Monster Slayer and Child Born of Water are represented in the sand paintings by their individual colors, black and blue. The color blue is associated with the lunar twin, Child Born of Water, who plays a key role in compensating the aggressive nature of his solar warrior brother. Campbell attributes the ultimate success of the twin heroes to the lunar twins mitigating influence: “One cannot help but feel … that it is largely the balancing presence of Child Born of Water which guarantees the benevolent end of [their] martial labors” (“Commentary” 63).

Water-Carrier is instrumental in assisting Sun-Father in administering the series of trials through which the twins prove their worthiness. In the sand paintings series, the twins have thus far remained identical in both form and color. The sixth painting depicts the pivotal point of transformation, where Sun-Father and Water-Carrier bestow upon the boys their proper names. It is at this moment also that they gain their individual colors and powers. Psychologically, this is the point at which the male ego becomes conscious of its dual nature. Hereafter, Monster Slayer and Child Born of Water are represented in the sand paintings by their individual colors, black and blue. The color blue is associated with the lunar twin, Child Born of Water, who plays a key role in compensating the aggressive nature of his solar warrior brother. Campbell attributes the ultimate success of the twin heroes to the lunar twins mitigating influence: “One cannot help but feel … that it is largely the balancing presence of Child Born of Water which guarantees the benevolent end of [their] martial labors” (“Commentary” 63).

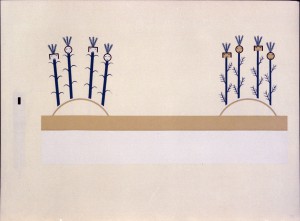

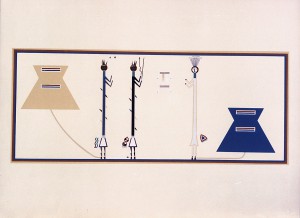

In the seventh sand painting, Monster Slayer and Child Born of Water now appear as four figures instead of two. At this critical point in the psychological process, the fourfold structure of the male Self emerges.8 Fully conscious of its dual nature, the solar-lunar male ego can now “see into” the masculine archetypes in the unconscious, as represented in the solar/lunar fathers. However, although the male Self has emerged, it is still in its untested version. Its archetypal power has been acknowledged but cannot be utilized until the ego is fully initiated.

In the seventh sand painting, Monster Slayer and Child Born of Water now appear as four figures instead of two. At this critical point in the psychological process, the fourfold structure of the male Self emerges.8 Fully conscious of its dual nature, the solar-lunar male ego can now “see into” the masculine archetypes in the unconscious, as represented in the solar/lunar fathers. However, although the male Self has emerged, it is still in its untested version. Its archetypal power has been acknowledged but cannot be utilized until the ego is fully initiated.

The eighth sand painting portrays the further development and strengthening of the solar/lunar ego. The legend describes the twins undergoing repeated testing to determine if they are worthy of receiving their sovereignty, symbolized by an eagle feather which their father bestows upon them.

The eighth sand painting portrays the further development and strengthening of the solar/lunar ego. The legend describes the twins undergoing repeated testing to determine if they are worthy of receiving their sovereignty, symbolized by an eagle feather which their father bestows upon them.

The third stage of Campbell’s hero’s journey, the “Return,” begins with the ninth painting. Having acquired the information and tools they need from their father, Monster Slayer and  Child Born of Water travel on a rainbow back to the earth realm to destroy the monsters. The next four sand paintings demonstrate their successful defeat of the monsters. Even in this final stage of their journey, they encounter formidable obstacles that require strengths and know-how they have yet to develop. They are humbled into admitting that they still need their dual fathers help to accomplish their destined purpose.

Child Born of Water travel on a rainbow back to the earth realm to destroy the monsters. The next four sand paintings demonstrate their successful defeat of the monsters. Even in this final stage of their journey, they encounter formidable obstacles that require strengths and know-how they have yet to develop. They are humbled into admitting that they still need their dual fathers help to accomplish their destined purpose.

In the psychological process, the individuating ego, once having gained awareness of its power, runs great risk of becoming over-inflated and narcissistic. The limitations inherent in Campbell’s heroic stage of consciousness have been explored at great length. It is widely accepted that the hero, or twin heroes, do not represent the highest state of transcendence. Campbell readily acknowledged that there is a danger in inflating the mythologem and getting stuck there. the way of the hero (ego) is better understood as a path to an even higher, and deeper, level of consciousness (the Self).

Jungian analyst John Beebe advises that while the hero stage may be a leap forward for individuals “at risk of drowning in the unconscious,” a continued identification with the Hero may persuade a person to feel an inflated sense of control over his unconscious and, consequently, to anticipate a degree of control over life that is unrealistic. Joseph Henderson distinguishes between the hero, “an archetypal stage in the unconscious, denoting the formation of a strong ego identity,” and the “true initiate,” who is associated with Jungian individuation.9

In the Navajo initiation myth, the twin heroes attain the status of the “true initiate.” The “Return” phase of the initiation allows for the male ego (hero) to understand its own limitations. Both solar and lunar aspects of the ego are repeatedly challenged and humbled by the knowledge of their boundaries.

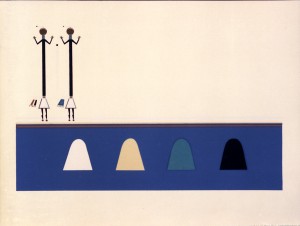

After defeating the monsters, Monster Slayer and Child Born of Water return to Changing Woman’s hogan, where they find their strengths strangely diminished. As their final heroic act, they record their healing journey in this series of sand paintings which are used by the Navajo people in warrior and healing rituals. With this final deed, their journey has comprised all requirements of the monomyth Campbell defined: 1) leaving the ordinary world for a supernatural region; 2) there meeting unusual forces and conquering them; and 3) returning with the ability to aid society (Hero 30). A congregation gathers around the failing twins and performs over them a ritual commemorating the successes and lessons of their journey. Through the healing power of the sand paintings, chants, and songs, Monster Slayer and Child Born of Water are fully revitalized. At this juncture in the psychological process, the solar and lunar aspects of the male ego are fully integrated. The final sand painting displays Monster Slayer and Child Born of Water again as four figures, each standing on a mountain of a different color. This configuration symbolizes the fourfold Self, which the fully initiated ego has now encountered.

The first stage of the coniunctio, the “union of the same,” is completed, and the solar/lunar ego is prepared to enter into a “union of opposites.” The remaining sand paintings in the series are used in the healing ceremonial but do not correspond to the sequence of events described in the story. While the myth ends here, many variants also show the twins eventually assuming places of leadership in the community.

The masculine initiation myth of Monster Slayer and Child Born of Water reinforced Campbell’s understanding that male mythology, and the male hero, have more than one side. Unfortunately, many critics of Campbell’s hero tend to see only one of its sides. If we approach Campbell’s hero from a solar/lunar perspective, we see that his popular single hero mythologem can be understood as a variant of the twin heroes archetype; whether single or twin, the hero incorporates both solar and lunar aspects of the masculine.

The masculine initiation myth of Monster Slayer and Child Born of Water reinforced Campbell’s understanding that male mythology, and the male hero, have more than one side. Unfortunately, many critics of Campbell’s hero tend to see only one of its sides. If we approach Campbell’s hero from a solar/lunar perspective, we see that his popular single hero mythologem can be understood as a variant of the twin heroes archetype; whether single or twin, the hero incorporates both solar and lunar aspects of the masculine.